NOTE: This is an amendment to an earlier review of the same film.

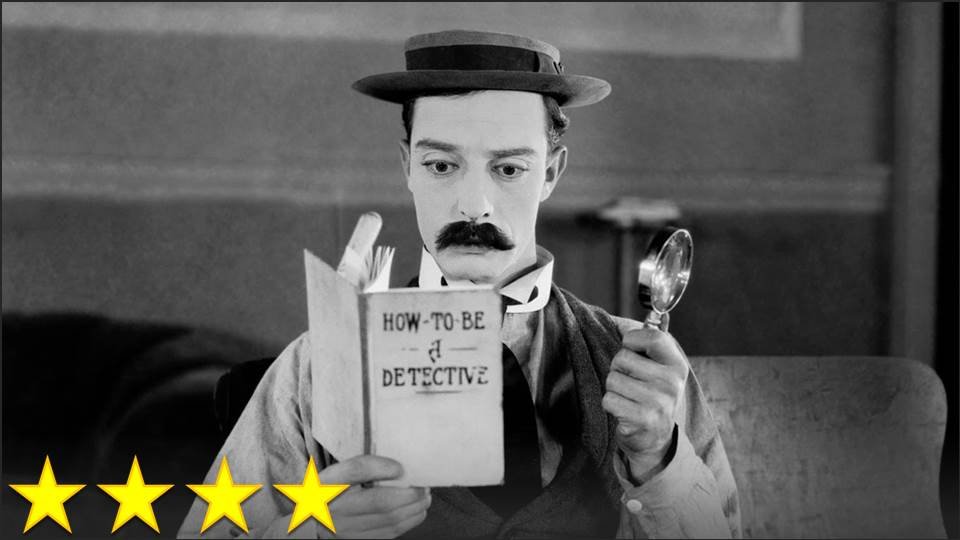

When I first watched this movie, it was the Giorgio Moroder version (a soundtrack comprised of ’80s pop that only sometimes fit the scene well). This is because I had little tolerance for silent cinema at the time, and while I still don’t think I’m very good at watching silent movies, I’m improving. The main reason why it made sense for me to return to this story is that the version I saw from back in the ’80s was missing so much of the movie – a lot of the film was lost and had yet to be restored. I didn’t realize that at the time, so I stupidly criticized Lang for the unintelligible plot that the incomplete version had (and felt quite ashamed when I learned within the month or so that followed that I had been so ignorant of such important information). The current (2010) version is missing only about five minutes, which is why it’s called “The Complete Metropolis” in some editions, and its plot is perfectly understandable and enjoyable. For this and other reasons, although I’m not changing the four-star rating I gave the film before, I think I appreciate the movie even more than I did years ago.

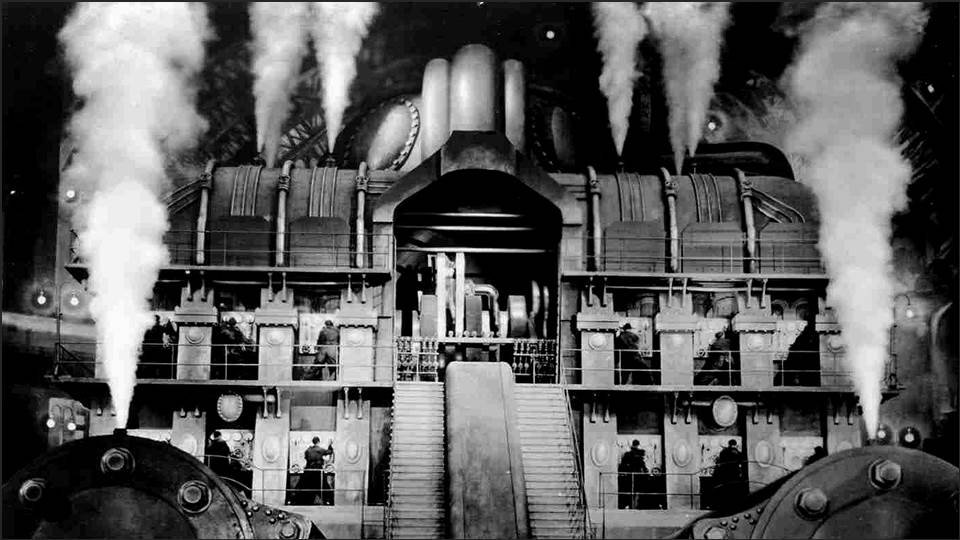

It is very clear that this is a unique work of art from the very beginning. The film’s opening – specifically the title card – is in and of itself worthy of praise, and it sets the exciting tone for the epic movie that follows. The film is structured in three acts, more or less, and the cards that tell us how far we are through the movie help to create the theatrical experience. The theatrical feeling – that is, the feeling of being at a stage show – makes me wish I could see this in the form of a musical, but I know that it is designed to serve a very different purpose. Lang is borrowing from theater to appeal to the people who would be too embarrassed to go to a film that didn’t resemble high culture in some way: the upper class. This project of making cinema something for intelligent and sophisticated audiences was very important to many German filmmakers at the time, and it is apparent in the relentless use of biblical references all throughout the film, even including the obscure Canaanite god “Moloch.” The protagonist is very much a Christ-like figure, but is also at least as much a Moses (since he is, more or less, the son of Pharaoh). Nods to the Tower of Babel are also mixed in, with Maria entirely reworking the story to support her thesis – an unsettling use of religion that sort of makes Maria, a very moral character, seem almost like a lying demagogue.

The film has such a strange mix of elements that I love and elements that I find frustratingly disappointing. The binary between the moral Maria who hasn’t a bad bone in her body (and who seems like she might as well be oblivious to the existence of sex) and the robot Maria who embraces all things sexual and wild is a great setup, but it would have been great for the two of them to have had an encounter. The protagonist is a fascinating character: he has a number of visions that make him either a madman or a supernatural prophet, and the has his most important vision – a nightmare sequence – after he wakes up, whereas any other film would show him having a nightmare and then waking up. It is actually this nightmare scene that makes the film work for me; it’s my favorite part of the movie because it builds up to such a satisfying climax of the second act, ending just as perfectly as the second Hunger Games film does. I can’t help but compare it to the film adaptations of Carrie, which send us into the third act with great anticipation to see how everything’s about to fall to chaos, “B-movie style,” although Lang gives us more hype before act three that makes it all that much better. The problem is that the third act doesn’t offer quite enough excitement to live up to this hype, instead feeling rather long. The ending, too, is not as satisfying as it could be, mostly because the message that the film keeps preaching about the heart being a “mediator” isn’t very meaningful (and I think I read somewhere that Lang himself didn’t sincerely believe it).

This issue of the vague thesis brings me to the question of what the heck this movie is supposed to be. Is it a utopia or a dystopia? I hear that Hitler loved this movie, but I can’t tell if it promotes fascism, socialism, democracy, or some other form of government entirely. Somehow this movie is very European and very American. It may be in black and white, but it is very colorful (although perhaps my memories of the lovely tints in the Moroder version have shaped the way I want to see this version). I can’t even tell what I’m supposed to think about technology after watching this film. It almost tries to undercut its every move, and yet it still manages to be a very satisfying experience. There’s a kind of energy in this film that’s infectious, and it’s the kind of movie that I just want to have on in the background all the time because I enjoy its essence more than anything else about it. After thinking about all of this, one thing has become more and more clear: this must, indeed, be made into a musical. Get to it.